July 24, 2015 by Steve Murray

A (not so) Missing Link – Between the Brain and the Immune System

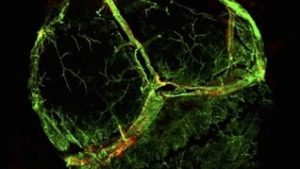

Newly-discovered lymphatic vessels, shown in red, were almost invisible behind larger blood vessels, shown in green (University of Virginia)

“They’ll have to change the textbooks.”

Scientists don’t hear this very often (if ever), but that’s the remark that came in response to a new discovery that the brain is connected to the immune system by vessels that no one knew existed.

The connection could change how neurological diseases like Alzheimer’s and multiple sclerosis are understood and treated.

Pathways for the immune system

The finding concerned lymphatic vessels, the pathways that allow immune cells to move through the body to fight infection and disease.

The lymphatic system is not, itself, a part of the immune system. Its role is to carry the fluid containing white blood cells (which fight harmful microorganisms) throughout the body and, finally, to excrete them. The lymphatic system, therefore, is essential to immune system functions. Medical scientists had concluded that the central nervous system (CNS) did not possess such a lymphatic drainage system.

Research work took place in the lab of Dr. Jonathan Kipnis, director of the University of Virginia Center for Brain Immunology and Glia (BIG). Dr. Antoine Louveau, a postdoctoral fellow in the BIG lab, examined the meninges (tissue membranes that cover the brain and spinal cord) of a mouse.

Although science accepted that some kind of immune system action took place in the meninges, they didn’t really understand how immune cells entered or exited the CNS.

“Any neuroscience textbook that has ever been written will say that the central nervous system is devoid of a lymphatic system,” said Dr. Louveau. “When we started our project, our question was if there are so many immune cells surrounding the brain, how do they traffic there?”

Dr. Louveau developed a technique of mounting the entire tissue covering onto a single slide that could then be viewed through a microscope. He first fixed the tissues within the mouse skullcap to maintain their intact physiological arrangement before dissecting them. He later noted that he might not have made the discovery if he had tried to do the dissection first.

When he noticed vessel-like patterns of immune cells in the meninges, he applied a fluorescent dye test for lymphatic vessels that identified them immediately. Dr. Kipnis noted that the vessels would normally be hidden behind another blood vessel, located in the part of the brain that scientists have difficulty imaging.

This research was published in the Journal Nature on June 5.

New directions for treatment

The ultimate value of the team’s work may lie in its implications for the study and treatment of neurological diseases ranging from autism to Alzheimer’s disease to multiple sclerosis.

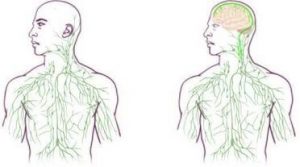

Lymphatic system maps: old (left) and updated (right) to reflect UVA discovery (University of Virginia Health System)

“The immune link with so many neurological disorders is now obvious,” said Dr. Kipnis. “If the immune system is involved with those disorders, [then] the communication between the brain and the immune system is mediated by these vessels. We believe that they probably will be found to play a major role in most, if not all, neurological conditions where the immune system is involved.”

Large pieces of protein accumulate in the brains of people suffering from Alzheimer’s, for example. These proteins could be accumulating because CNS lymphatic vessels don’t efficiently remove them. If that model is accurate, then it may be possible to treat such disorders with therapies that target the brain’s lymphatic vessels.

According to Dr. Kipnis, this discovery could change the way we perceive neuroimmune interaction.

“We always perceived it before as something esoteric that can’t be studied,” he said. “But now we can ask mechanistic questions.”

Next steps

Dr. Louveau says that the research will now go in two directions. The first challenge is to confirm that the same kind of lymphatic network exists in humans, so that focused disease research can proceed. The second, and likely more ambitious challenge, is to understand the role of these vessel in the broader context of neurological pathologies.

Work like this will guarantee more than revised textbooks; It will guarantee entirely new ones.

Primary source:

Researchers Find Textbook-Altering Link Between Brain, Immune System